Overview

Research and

Collections Consulted

Early Mining Era

1850s to 1920

Michigan Tech & the Student

Experience 1930-1990

Personal Stories of Note

ks |

Early Mining Era (1850s to 1920) |

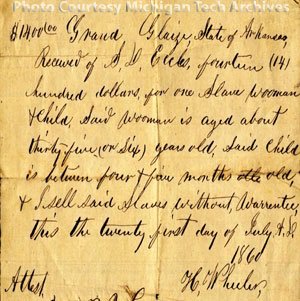

Figure 1 |

Though a slave receipt (Figure 1) was found in the archives collections, as far as can be established reliably, all African Americans who came to the Keweenaw, even before 1865, had either been freed previously or were born free. According to a census summary published in the Portage Lake Mining Gazette from February 21, 1863, there were 37 “free colored” men, and 25 “free colored” women in Houghton County in 1860, when it still included Keweenaw and Baraga Counties, out of a total population of 18,468 in the same area, meaning ~ 0.3% were black. One example of an early African American resident connected to the Copper Country is William Gaines, who was a freed slave. He and his wife briefly lived in Houghton in or shortly before 1855, where he worked in the early pit mining operations. Gaines was a freed slave from Virginia, who was sent to the Upper Peninsula by his former owner and biological father, shipbuilding magnate Pitt Gaines, likely because the remote reaches of Lake Superior were one of the few places where former slaves could pursue fruitful lives without being in real danger of capture by bounty hunters out to retrieve “runaway slaves,” which also included the occasional retaking of previously freed men. However, after being injured on the job, the couple relocated to Marquette in 1855. (Northern Roots, pages 40-41). John Gaines was still in Marquette in 1870, but interestingly, his wife Mary seems to have returned to the Copper Country, where she lived in Webster Township (mostly corresponding to modern Chassell Twp. and the northeastern part of modern Portage Twp.) with her three children, owning around $200 worth of personal estate (1870 census).

|

|

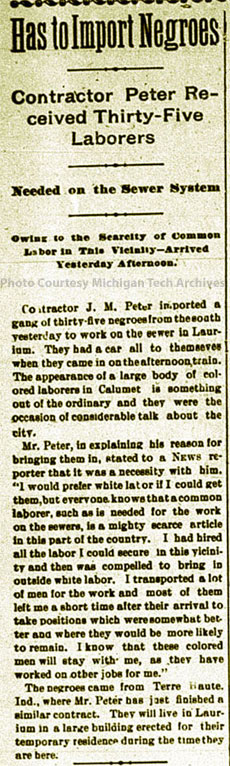

Even after the end of slavery on a national level, some African Americans were still arriving in the area as contracted laborers, sent here by their employers without necessarily having any personal desire to settle in the Keweenaw. An article in the Copper Country Evening News from June 1899 (Figure 2), details how a local contractor was building the sewer system in Laurium and had to import “a gang of thirty five negroes from the south”, because he could not recruit enough help locally (likely because the copper mines still provided an overabundance of better paying, more secure jobs). The news article stresses how unusual a procedure this was, however, and that the black workers were only to be in the region temporarily.

< Figure 2

News article from the 06-28-1899 Copper Country Evening News reporting That Local contractor J. M. Peter “ has to import negroes”, due to his failure to secure enough white laborers.

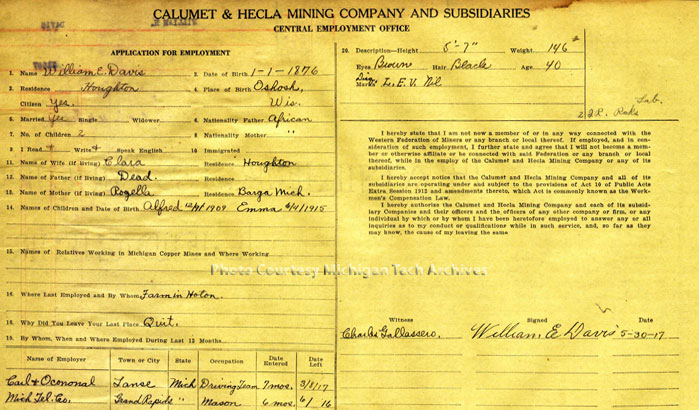

While we can certainly assume that, just like their white counterparts, many African American pioneers were attracted by the prospect of employment in the mines, surprisingly few actually were employed as miners. If this is due to institutional racism on part of the mining companies, or a lack of interest on part of the African American settlers, is unclear. The 1864 Michigan state census identifies only two black individuals as miners, and the federal censuses for 1860 and 1870 list none of the identified black or “mulatto” individuals as miners. Even at a later time period, after 1900, we can only place one individual identified by name into the copper mines for a very brief period in 1917 (Figure 3). Rather, a great number found work as laborers in the industries ancillary to underground mining operations, and even more so in the service sector. For instance, the 1860 and 1870 federal censuses list the following occupations for adult black individuals in the area: laborer (10), servant (14), housekeeper (9, all women) cook (8), hotel keeper (1), fireman (1), huckster (1), bookkeeper (1) and, importantly, barber (10). |

Figure 3

Calumet & Hecla Mining Company employee card for William E. Davis, one of the few African American individuals identified by name to have worked in the local copper mines. He only stayed with C&H for a brief period. |

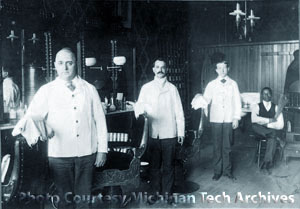

Figure 4

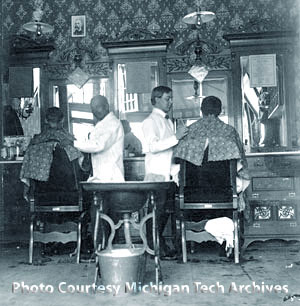

Nara 42-149: Barbers inside a turn of the century barber shop. A young African American gentleman is seated towards the back holding a whisk broom.

Figure 5

Nara 42-098: Interior of a barber shop with two barbers at work, one of whom appears to be African American; the portrait on the wall appears to be King George V, so the picture likely is from sometime after 1910, and the owners ought to have a strong connection to the British Empire. Incidentally, a prominent black barber in Houghton, A. R. Richey and his second wife were Canadian born. A. R. senior died in 1896, and his son A. R. junior took over the store. There is a possibility that he is the man on the left in this picture. A.R.’s wife was Canadian too, so it would not at all be surprising for the family to hold Canada’s monarch in high esteem. However, the description for the photograph in the Keweenaw Digital Archives states the location is probably in Calumet, which speaks against the Richey’s whose store was in Houghton.

Figure 6

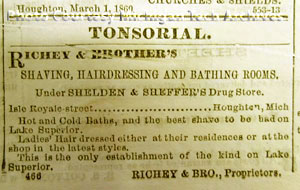

Newspaper advertisement for Richey & Brother’s (Portage Lake Mining Gazette, 04-29-1869).

|

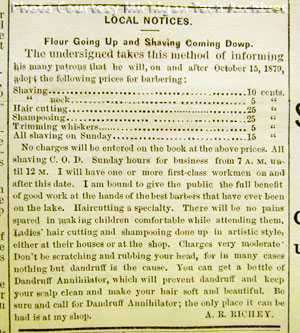

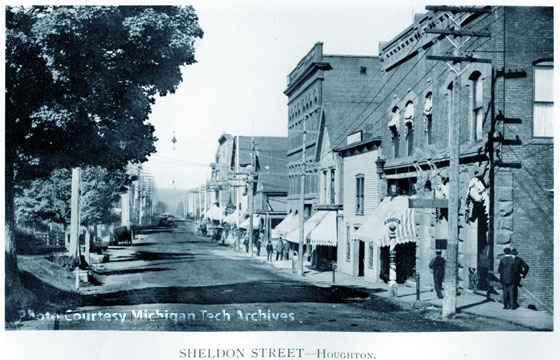

The barber business seems to have been of special significance among the service professions. Quite a number of black people were working as barbers throughout Michigan at the time (Michigan Manual, page 106), and by 1910 there were 272 barbers and hairdressers among the adult male African American population in Michigan, one of the highest counts for individually listed professions (Michigan Manual, page 310). We know of at least 12 black individuals who worked as barbers in the Copper Country before 1900. There seems to have been much demand for their services. Sanborn Perris insurance maps from the 1800s indicate that at any given time there were at least three or four different barber shops operating simultaneously in the modestly sized village of Houghton. Some of these were run by white barbers, but black barbers were just as prominent. We have ample evidence that at least in the Keweenaw, black and white barbers would routinely work alongside each other in the same shop (see Figures 4, 5), and employ each other. Regardless of their own race, they all catered to the general population, which was, though ethnically diverse, overwhelmingly white. In fact, almost all of the black barbers actually drew the “color line”, refusing to serve people of their own race for fear of losing the business of white customers (Michigan Manual, page 106). The opposite phenomenon of black barbers specializing in cutting primarily black people’s hair seems to only have evolved after the First World War (compare Michigan Manual, page 106). Also of interest is that in this early period, black male barbers would often serve men and women alike, and at times explicitly stated their proficiency in dressing women’s hair in the latest fashions in their advertisements (Figures 6, 7). Significantly, at the time many barbers also offered hot baths (Figures 6, 8), something that would certainly have been appreciated in a mining region, where smelters filled the air with soot, and many households still lacked indoor plumbing.

Figure 7

Newspaper advertisement for A. R. Richey’s barber shop, including price list (Portage Lake Mining Gazette, 10-16-1879).

|

Figure 8

Book F572-S9-A7-pt 4-5: View of a portion of Shelden Street looking west, likely from the 1890s. Note the barber pole and “Baths” sign in front of Western Union building. The new Houghton National Bank from 1888 is also in the shot, therefore this barber shop is likely not Richey’s. |

|